| First Officer Petersen - Am

Deutschen Wesen soll die Welt genesen Titanic (1943) |

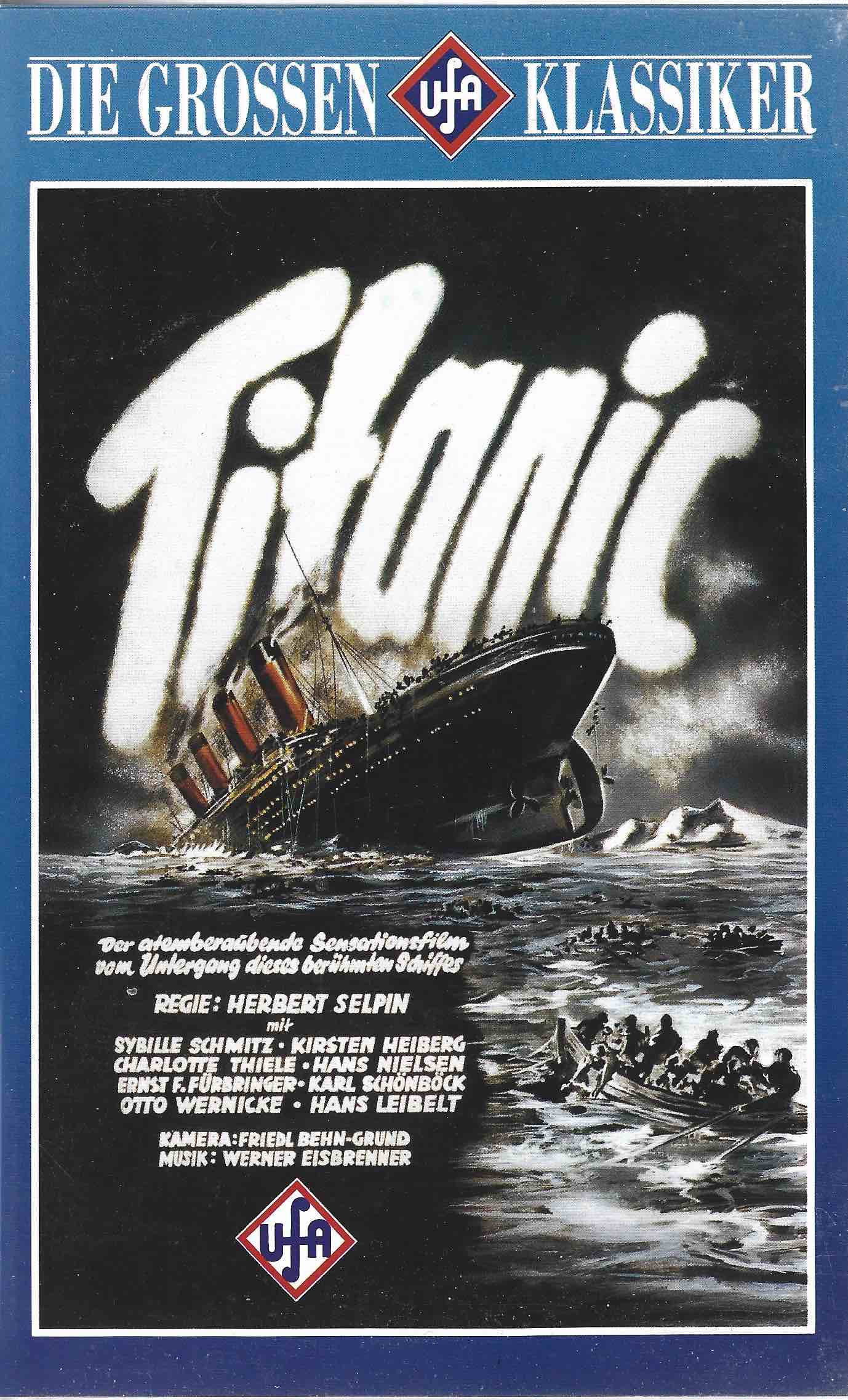

Cover of my copy of the video |

| Background By the time the 1943 film Titanic was created, a considerable tradition of retelling the story of the sinking of the Titanic existed in Germany starting with the 1912 film In Nacht und Eis. The 1920s saw the publication of two fictional memoirs. Max Dittmar-Pittmann claimed to have been the third officer of the Titanic. H. Hesse alleged he had been one of the ship's electricians. Max Dittmar-Pittmann also toured through Germany in 1929, giving lectures about his adventurous life and his experience on the Titanic. In 1929/30, the film Atlantik was shot in German, English and French and though avoiding the name Titanic it was clearly a fictionalised retelling of the story. It was the first talkie to be released in Germany. SOS Eisberg (1933) by Leni Riefenstahl and Arnold Fanck, though again not about the Titanic, introduced the sea-drama format to film.1 The 1930s also saw the publication of three novels based on the story of the Titanic. While one novel, Bernhard Kellermann's Das Blaue Band avoided the name Titanic, it was inspired by the story and the mythical attempt to win the Blue Riband on her maiden voyage. Robert Prechtl's novel Titanensturz (later renamed Der Untergang der Titanic) was published in 1937, followed, in 1939, by Josef Pelz von Felinau's novel Titanic. Die Tragödie eines Ozeanriesen. Both novels were influenced by Dittmar-Pittmann's memoirs, as discussed in the pages about Third Officer Erikson and Third Officer Hans Erik Petersen. |

| The story of the Titanic

was therefore well established as was the

presence of a German officer on board when

Reichsminister für Public Enlightenment and

Propaganda Joseph Goebbels decided to turn the

story of the sinking of the Titanic into

a piece of anti-British propaganda. Why the sinking of the Titanic had a greater echo in Germany than in some other countries was arguably due to the fact that Germany like the UK and the US had a significant maritime heritage, a dominant Protestant culture that valued self-denial and civil duty, a long history of emigration to the US, and aspirations to become a naval power.2 Just as in the UK and the USA, the tragedy of the maiden voyage of the Titanic which ended with great loss of life was discussed in parliament and written about by poets and columnists. |

| Sources While Pelz von Felinau's novel is well known to be a source for the film, less attention has been paid to the slightly earlier novel Titanensturz by Robert Prechtl which also provided inspiration to the film: J. Bruce Ismay pushes for a record crossing to ensure that the Titanic wins the Blue Riband to solve the White Star Line's financial difficulties caused by J. J. Astor's attempt of a hostile take-over of White Star Line. These alleged causes for the sinking of the Titanic feature strongly in both Prechtl's novel and the 1943 film. The difference between them is that Prechtl's narration has Astor come through the events a wiser person who proves to be a hero when tragedy strikes. The 1943 film depicts Astor without redeeming features, even his marriage with Madelaine is cold and ultimately destroyed by his preoccupation with ruining Ismay and his suspicion that she gave her jewellery case to the impoverished Lord Douglas. Only after she left him, he discovers that he suspected her wrongly. The myth that the Titanic was attempting to win the Blue Riband is mentioned in Prechtl and Pelz von Felinau. It was a wide-spread story that is still repeated today (see Officer Merry). Pelz von Felinau’s novel also mentions the Blue Diamond and that Astor wants to set it in some jewellery. |

| Pelz von Felinau was involved in

the first stages of developing the film. It is

likely that Max Dittmar-Pittman had been exposed

as an imposter by this time, and it was this

development that prompted the makers of the film

to rename the German officer Petersen and give

him a promotion to first officer. The Film When First Officer Petersen first appears in the film, Lightoller asks how a single German officer has ended up on board. He is given the same explanation as in the novels. Petersen was hired because the original officer who had falling ill, with appendicitis in this case, and because Captain Smith knew him. The fact that he is German has to be mentioned as otherwise the audience would not be aware of the fact, as everybody is speaking German. Petersen’s loyalty to the White Star Line questioned due to his nationality. Unsurprisingly in a war time propaganda film, Petersen is the only clear-sighted officer, while Captain Smith and the other officers ignore all warning signs. |

| Petersen is constantly warning of

the dangers ahead and is the only one who dares

to contradict Ismay. He even breaks his rigid

principle to never do anything that is against

the rules and enters a passenger's cabin to

plead with Sigrid Olinsky to use her influence

on Ismay to reduce speed. He is the only

one who sees the real danger that lies ahead and

acts on it. Considering its sources, it is unsurprising that the film is far from historically accurate. To name but one instance: when the iceberg is sighted, Murdoch does not immediately take evasive action but orders one of the searchlights to be turned on. The real Titanic did not have any searchlights. The searchlight’s filament, however, breaks almost as soon as it is turned on, and there is no replacement on board. Both Prechtl’s and Pelz von Felinau’s novel criticise the inadequate equipment of the Titanic. |

|

After the sinking of the Titanic,

Petersen heroically saves a little girl and

swims with her to a lifeboat, echoing the

reports that Captain Smith swam with a small

child to a lifeboat. The same role is given

the second officer Lanchester in the British

version of Atlantic. In the German version

of Atlantik, the Captain orders First

Officer Lersner to try to save a child left

behind on board and take it to a lifeboat.

Unlike Captain Smith, who

refused the offer to get into the

lifeboat, Petersen accepts the offer

and gets into the boat. He does not do

so for selfish reasons, of course, but

to be able to tell the truth about the

ruthless behaviour of Ismay and bring

justice for those who lost their

lives.

|

|

It is the final court room scene

in which Petersen accuses Ismay and the others

responsible directly, but the court decides to

only blame the dead Captain Smith. The final

title card reads 'The death of 1,500 people

remained unatoned. An everlasting condemnation

of England's lust for profit.'3

|

| An interesting question is the

nationality Petersen's love interest Sigrid

Olinsky. Most English descriptions call her 'a

Baltic German'. In the film, Captain Smith

describes her as 'eine reiche Baltin' (a rich

Baltic woman). One linguistic point to make

here is that in English the sea east of

Denmark is the Baltic Sea, in German it is the

Ostsee. In German only Lithuania, Latvia and

Estonia are Baltic states, while in English it

is possible to refer to Mecklenburg-Vorpommern

(in Germany) as a Baltic state. What

nationality Sigrid Olinsky has is further

complicated by history. In 1912 the eastern

part of the Baltic states were part of the

Russian Empire, the western part was part of

the German Empire, roughly up to Klaipėda, or

Memel as it was called then, in Lithuania. What exactly do we learn in the film about Sigrid Olinsky? First, there is the telegram she receives: Sigrid Olinsky - SS Titanic Vermögen eingezogen, Güter beschlagnahmt, Gregor Sibirien Verbannt, Rückkehr unmöglich, Fedor (Sigrid Olinsky - SS Titanic - Assets confiscated, property seized, Gregor exiled to Siberia, return impossible, Fedor) Since, according to Captain Smith, Sigrid Olinsky is not married, who is this Gregor who is exiled to Siberia? He is certainly a Russian subject, otherwise he would not be exiled to Siberia. We learn from the men who introduce the most interesting characters, ‘Sie soll ungeheure Ländereien in Russland haben.’ [She is said to have enormous estates in Russia.] Sigrid Olinsky is therefore, like Gregor, a Russian subject but could nonetheless be German-speaking, as the Russian Empire was a multi-ethnic state.4 Whether German- or Russian-speaking is impossible to say. |

| Interestingly, John Jakob Astor

and his wife Madelaine become Lord and Lady

Astor, at least according to official

programmes, thus becoming British citizens.

Bruce Ismay is turned into Sir Bruce Ismay,

though he was never knighted in real life. An

explanation is that all greedy men are

depicted as British. However, one point that I think undermines this attempt to turn all the villains into British people by the fact that everybody in the film speaks German. A viewer may not even be aware of the fact that the bad guys are supposed to be British and the good guys German. (Nobody speaks with a British accent, which would have clarified the point.) Britain was generally regarded as a kin nation, unlike the Slavic states who were considered a lower 'race'. As Koldau points out, minor characters like Jan and Anne, the devoted couple in steerage, could just as well be Scandinavian as German.5 |

| Nazi propaganda? The film is often described as a Nazi propaganda film, but is it really? I have been questioning this assertion, while at the same time wondering whether my assessment is correct or just the result of the version of the film I knew missing the last part cut on the insistence of the British authorities in 1950. But having watched the full-length version I still wonder whether ‘Nazi propaganda’ is the correct term to describe the film. It is certainly a propaganda film made during the rule and on the initiative of the Nazi regime But is it 'just' anti-British propaganda or does it contain specific Nazi views and messages? |

| Racism is definitely present in

the film, with Marcia the 'gypsy' girl and the

'Levantine' in steerage. But racism was part

of the narration of the Titanic right

from the start. From Harold Lowe's statement

at American Inquiry that he fired his gun to

scare off 'Italians, Latin people' who 'glared

more or less like wild beasts'.6

In his memoirs Lightoller asserted that the

men he had to chase out of a lifeboat were not

'British, nor of the English speaking race'

but 'Dagoes'.7 The

1929 film Atlantic, which while not

officially set on the Titanic is

obviously echoing its sinking, only the

foreigner 'Dandy' panics, and among the men

trying to storm a boat is a black man who is

shot dead.8 Racism

is certainly present in the 1943 film, but

relegated to some subplots. One could also ask

which film from this era is not blighted by

racism from a modern perspective. Titanic also includes some antisemitic tropes, according to several studies of the film. Köster and Lischeid write that the criticism of stock market manipulation is antisemitic,9 according to Koldau and Richards 'the Levantine' is coded as Jewish,10 The Strausses or Benjamin Guggenheim were omitted as their stoicism did not agree with the national socialists' view on Jews.11 I never made this connection, but 'In the end, film propaganda is no good at shaping opinion, just reinforcing already existing opinions.'12 |

| Just because one doesn't notice

something is propaganda does not make it not

propaganda, that is the devious side of

well-made propaganda after all. But Malone for example

states that the film fails as propaganda.13 The fact that

Petersen is German is mentioned only twice

and, as mentioned before, the nationalities of

many characters are far from clear. Are Jan

and Anna German or Scandinavian? It is never

made explicitly clear in the film. Henry and

Bobby could be German with English sounding

nicknames. The main focus of propaganda was anti-British, as such it did not work very well if the viewer did not already have anti-British sentiments. |

| For the Nazis the end result was

not satisfactory. It was not released in

Germany itself, but with great success in

occupied territories and allied countries. The

exact reasons are not known but one

explanation is that the tale of a great ship

doomed thanks to its arrogant captain could be

regarded as a parable of the current state of

war, in which a society was led into disaster

and destruction by an overconfident leader. |

| After World War II How a film is viewed also

depends on one's own perspective. The

history of the film after the end of World

War II is also revealing. It was first

released in what was about to become the

German Democratic Republic as the Soviet

authorities appreciated film's criticism

of rapacious capitalism.

When the film was released in the American and French zones of Germany in December 1949, the British authorities heard the anti-British propaganda loud and clear: 'The film was obviously made with the direct object of anti-British propaganda. Although the propaganda is too apparent to be believable, the film achieves a subtle effect in that everyone knows the story to be founded on facts.'14 The news of the film's release created furore in the British press. Without any information about the film's content or message, several papers 'proceeded to invent the most lurid and sensational accounts. Nevertheless, many of these wildly inaccurate stories have been absorbed into the folklore of that event and passed down to the present day.'15 |

| The outcry reached such levels

that the British government felt compelled

to demand that German chancellor Konrad

Adenauer order the film to be withdrawn from

cinemas. Adenauer pointed out that he could

not do this, as the new constitution had

specifically restricted the influence of the

government on the arts. As the British continued to work for the film to be banned and word about these efforts spread, many Germans rushed to the cinema, out of curiosity and to see the film before a ban took effect.16 The film was banned on 1 April 1950. Apart from the anti-British message the British authorities had detected, another factor for the ban of the film, alongside the pressure built up by the press who exaggerated the anti-British propaganda of the film, was, as Peck points out, that any film depicting the British mercantile marine in a bad light was violently opposed by the mercantile marine, starting with the film Atlantic, and probably scuppering David O. Selznick's plan for a film about the Titanic.17 |

| Even decades later different

people view the film very differently.

Jeffrey Richards judges that 'The Germans

all behave with honour, decency and

stoicism', while 'the British are the

villains'. Robert E. Peck points out that

'the officers all show up rather well during

the disaster - cool, efficient and

professionally competent.' In fact, he

concludes, 'Most viewers today, however, in

whatever country, would little suspect that

it had ever caused any problems.'18 In 1955, the film’s ban was lifted in Germany, but only the abbreviated version was shown. In fact, on the video tape I bought at the end of the 1990s the court scene is still missing. The film has been shown on German TV repeatedly and is freely available to buy, unlike proper Nazi propaganda like Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph des Willens, though slowly these bans are lifted. Moreover, in the days of the internet and Youtube, banning a film is almost impossible. |

| When a film depicting a

historical event is taking liberties from

the fact and is criticised for this, the

reaction is often, 'But it's just a film,

not a documentary'. Unfortunately, many

people do not question which part is

authentic, and which is not. Many Germans

regarded the film as a true depiction of

events. German Titanic researcher

Susanne Störmer recalls how several people

in Germany asked her why Cameron left out

Herrn Petersen from his blockbuster film.19 The scenes of the flooding engine room were reused in A Night to Remember.20 |

| 1.

Biel, Down with the Old Canoe,

p. 149. 2. Bergfelder and Street, Titanic in Myth and Memory, pp. 3-4. 3. Koldau, p. 103, Richards, The Definitive Titanic Film: Night to Remember, p. 21, has 'unavenged.' 4. Wikipedia tells me that Olinsky is the name of two districts in the Russian Federation. In his criticism of the release of the film in West Germany in 1940, Brigadier William Crowe described Sigrid Olinsky as 'ex-Russian', Robert E. Peck, 'The Banning of Titanic', p. 431. 5. Koldau, The Titanic on Film. Myth versus Truth, p. 104. 6. Sheil, Titanic Valour, p. 91. 7. Lightoller, Titanic and Other Ships, p. 186. 8. Richards, A Night to Remember, p. 14. 9. Werner Köster and Lischeid Thomas (eds.), Titanic. Ein Medienmythos, p. 134. 10. Koldau, p. 106; Richards, A Night to Remember, p. 20. 11. Koldau, p. 98 12. Malone, in Bergfelder and Street, p. 128. 13. Malone, p. 126. 14. Peck, Banning Titanic, p. 431. 15. Peck, Banning Titanic, p. 435. 16. Peck, Banning Titanic, p. 435-440. 17. Peck, Banning Titanic, p. 441-42. 18. Richards, A Night to Remember, p. 19; Peck, Banning Titanic, pp. 432, 442. 19. Störmer, Titanic - Eine Katastrophe zwischen Kitsch, Kult und Legende, pp. 32-33. 20. Richards, A Night to Remember, p. 18. |

| Back to Fictional

Officers of the Titanic |