| Officer Esther Bailey - the

Unthinkable Officer Giselle Beaumont, On the Edge of Daylight. A Novel (2018) |

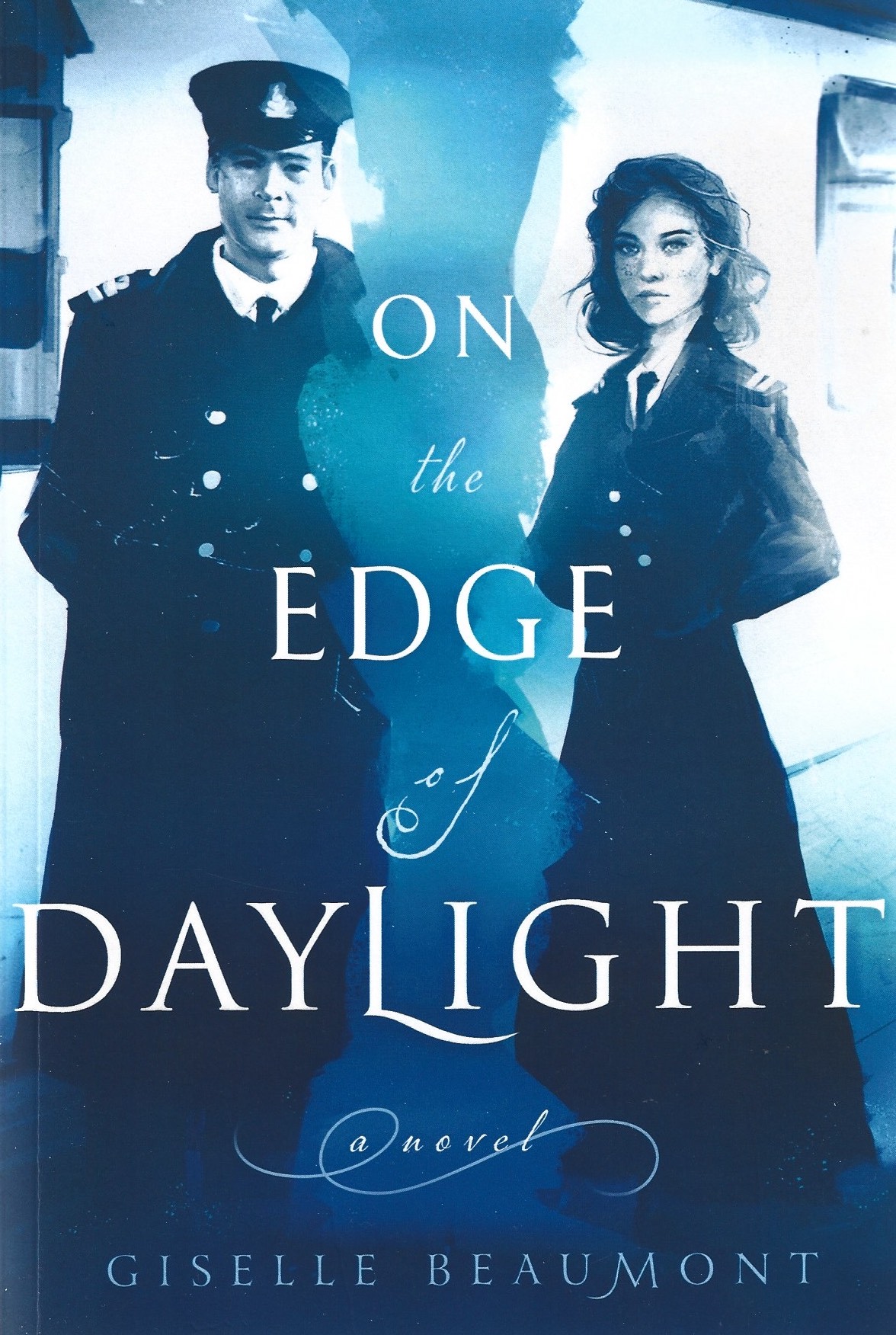

Cover of my copy of the book |

| A Female Officer on the Titanic?

Fictional officers of the Titanic have a long and varied history, so it was perhaps only a matter of time before somebody invented a female fictional officer. Here she is: 7th Officer (in training) Esther Bailey. More than a century after the events described in the book, some may find it incredible, but in 1912, a female officer was not 'nearly unthinkable' (as the author lets Lightoller think) it was unthinkable. The only way a woman may have become an officer is if she had lived as a man for the entire time of her apprenticeship. And it is highly unlikely that she would have been able to hide her identity long enough. There have been women living as men serving in navy and army during the Napoleonic wars and also in the armies during the American Civil.1 But times had changed. Additionally, these women almost exclusively were holding positions less exposed than officers. A woman in men's clothing might have become a steward or perhaps even an able seaman on the Titanic but not an officer. |

| In the 'Historical Note' Giselle

Beaumont writes that while there were no women

as officers on the Titanic, 'a few

underwent officer and maritime education during

this time period.' Where, I wonder. Beaumont

next mentions the WRNS, the Women's Royal Naval

Service founded at the end of 1917, as a good

point to start if you are interested in women in

the navy. Only five years may have passed

between the events described in the book and the

foundation of the WRNS, but the world had

changed completely. World War I was in its third

year when the WRNS was founded. A shortage of

men persuaded politicians and the admiralty to

employ women to free able-bodied men for combat

duty. The work women serving in the WRNS were

allowed to do was also a long shot from serving

as deck officers. The first roles they were

given was as cooks, stewards, and cleaners.

Later they were employed in a larger variety of

positions from drivers to mechanics, telephone

operators, electricians, and engineers and even

later gas mask inspectors and depth charge

workers. However, their work was exclusively on

shore, 'never at sea'. A restriction that was,

at least officially, not lifted until 1990. The

WRNS was disbanded soon after World War I ended.2 For all the emphasis the author puts on this book being a tribute to the people she writes about and respect, it is rather grating that her depiction of the officers is quite off from what we know about them. - Lightoller a stickler for rules? And why does she describe Wilde as an 'oaf'? Her treatment of Murdoch is everything but respectful. |

| In the 'Historical Note' Giselle

Beaumont admits that her depiction of the

officers is somewhat off. I assume she wrote

most of the story before she did a considerable

chunk of her research. Changing all that later

is a task that may require basically rewriting

the whole story so I can understand why Beaumont

left it as it is. Some changes, however, would

have been easy to make retrospectively. Harold

Lowe was a teetotaller, and replacing the pint

of ale he is holding with a cup of tea or a

glass of water would only take a few seconds. A strange aspect of the story is also that instead of completing a long apprenticeship that included theory but was mostly practical Esther Bailey studied maritime law for four years. This may have allowed a woman to become a lawyer specialising in maritime law but not a ship's officer. Seamanship was not something you learned at school or university. |

| Beaumont also invents an 'inclusion

initiative' of a maritime institute that allowed

Esther Bailey to study, but the idea is just

utterly ridiculous. (A friend of mine actually

googled 'inclusion initiative' in relation with

1912 and unsurprisingly came up with 0 hits.)

The WRNS was no 'inclusion initiative' but a

necessary step to enlarge the workforce and free

men for combat service. I don't claim to know exactly what a junior officer was doing at the various stages of the ship’s voyage, and I would have to do a lot of research to know, for example, the exact preparations made when a ship was in harbour preparing for the next, or in this case, first journey. But a junior officer's role would be helping with these preparations and not stay on shore and kick her heels as Esther Bailey does. There certainly was no need for a senior officer to stand around on the bridge to contemplate the vista. The role of a junior officer was also not to tag along with a senior officer as Esther Bailey is described as doing. |

| Esther Bailey is often described as

'cheeky' or 'witty' which is supposed to make

her somehow endearing. However, this kind of

behaviour would not have been tolerated from any

subordinate, leave alone a woman.

The whole attitude of both Esther Bailey herself and everybody around her is completely wrong for this period of time. I thought, while reading the book, that the way people react to the appearance of a female officer was not that of people in 1912 but of the 1970s and 80s. 'Women already can vote and work without their husband's permission. Now they want to become ships’ officers? Where will this emancipation nonsense stop?' |

| ‘A Vessel for the Reader’ In the 'Historical Note', the

author explains her reason for introducing

this fictional officer was to introduce the

reader to the strange world of shipping in

1912. Or as Beaumont puts it: 'Esther [is]

serving as a vessel for the reader by

introducing the duties of a White Star Line

officer from an outsider's perspective.' But

that job could be given to anybody:

journalist, detective, or curious kid. In

fact, many such fictional characters do just

that and also let the reader be present on the

bridge when the Titanic hits the

iceberg. The actual reason for introducing

fictional officer Esther Bailey is to allow

for a steamy romance between her and First

Officer Murdoch. What a reader will make of

that is up to them and reactions are surely

very different from one person to the next. I

personally found the sex scenes cringeworthy.

In 1912, a woman who would display such

enthusiasm and experience in bed would have

also immediately disqualified herself from any

consideration as a serious partner for most

men.

There are many nit-picky

comments about flaws in the story that

I could make - from the weather in

Southampton being described repeatedly

as freezing to the moon shining at

8pm, way too early, on the day before

the Titanic disaster when

there was famously 'no moon, no wind'

at twenty to midnight - but that would

make this excessively long. And does

it really matter that Southampton

Water as viewed from Southampton port

hardly qualifies to be described as

'vast stretch of sea', or that at half

six in the morning on 10 April, almost

twenty days after equinox, it was not

'dark as pitch' in Southampton. And

seriously? Murdoch 'waded close beside

her' after they were washed off a

collabsible into the sea. These errors

are not really important but those are

the thing I notice.

|

|

Yet another odd feature of this

book is that the author is quoting Cameron's

film verbatim towards the end of the

story. This certainly shows the enormous

influence this film still has on the popular

imagination.

Esther Bailey does not join other fictional characters on Collapsible B, but her brother Booker Bailey does. |

| Altogether, a female fictional

officer is certainly an interesting addition

to the list of fictional officers of the Titanic.

Perhaps there will be more in the future. |

1. see for example Deanne Blanton and Lauren M. Cook, They Fought Like Demons. Women Soldiers in the Civil War (New York and Toronto, 2002); Suzanne J. Stark, Female Tars. Women Aboard Ship in the Age of Sail (London, 1996). 2. Hannah Roberts, The WRNS in Wartime. The Women's Royal Naval Service 1917-45 (London, New York 2018). |

| |

| Back to Fictional Officers of the Titanic |